This is a response to "C isn't a Hangover; Rust isn't a Hangover Cure" (original Medium link) by John Viega.

# Context

A couple months back I read "C isn't a Hangover; Rust isn't a Hangover Cure" (original Medium link) by John Viega. I responded to the post already on Twitter (sometimes known as X) and in hindsight should have just written a blog post to begin with since the platform is so terrible for longform comment.

What follows is hopefully a more organized, digestable, and better response to John's post than what I wrote on Twitter. If you haven't read his post, I recommend giving it a read for full context instead of reading just what I've decided to directly respond to.

John's post goes into some concerns about using Rust and if Rust is really the right choice over something GC'd, and covers a few angles including whether memory safety really matters for you, what language best fits your team, and something that came up multiple times is dependency usage.

I disagree with some of the arguments John made surrounding dependencies and I frequently hear similar sentiments said by crowds who are anti-Rust. The idea that a program is less desirable or less secure because it has more dependencies. I find these arguments to be an easy jab lacking substance, and wanted to take an opportunity to challenge them.

My big complaint with John's points is that he spells out negatives but ignores most positives, instead telling the reader to figure those out for themselves.

It's important to understand who I am for a frame of reference: my background is in security and I first learned to program in C# making tools for Xbox 360 modding. That involved some reverse engineering and learning C++ for writing trainers/tools/cheats or whatever stuff would have to run on the console. Following my Xbox hacking in my teens, I professionally did web dev for some years (PHP), then web security, then hypervisor security at Microsoft, and now native code security focused on mobile applications. With the exception of my ~3 years in professional web dev, my title has always had "Security Engineer" in it -- not "Software Engineer". I sure as shit write a lot of code though.

I was entirely self-taught in programming at age 13 mostly through following online tutorials, and got a bachelor's degree in computer science.

My language of choice for about 8 years now has been Rust. This was settled upon after trying Go, D, Python, and some other languages inbetween. I am nobody in C/C++ circles and I'm a nobody in Rust circles, but I do pay close attention to the Rust community because I love the language.

# Why are dependencies seen as insecure?

John talks about this at good length and it's worth reading his thoughts. If you're too lazy to do so, I think it can be sufficiently summarized as:

- "Code review is a lot harder to do well than writing code"

- Dependencies can come from anyone and can generally be contributed to by anyone. Therefore the more dependencies you have, the larger your implicit circle of trust, and any break in that circle breaks your security. They become a single point of failure.

- You trust the code you write, and you know the code you write.

On #1, I don't agree -- at least not broadly. It's probably true for small bits of code that you have the technical know-how to write yourself, but in memory-safe langauges what's the worst thing you can miss in a code review of something that's not technically complicated? Probably minor bugs that would cause a DoS. So you bring in a dependency that you didn't audit super closely and now you have a DoS in your application. Depends on your threat model how important this is to you, and whether that impacts your mental quality rating of the dependency.

On #2 I mostly agree. You are opening up your circle of trust, but done right you can protect yourself. The npm left-pad incident is a prime example of what can go wrong from even a non-malicious dependency failure.

In the left-pad incident a package named "left-pad" was removed from the npm registry causing widespread build failures for almost every node.js application. The broad usage of this dependency shocked people since it was less than 50 lines of code and could be written by anyone.

If you're pulling in a dependency that's already compromised then you're a bit late, but for avoiding future compromise you can:

- Use a package service that does not delete yanked dependencies. This should only be possible in extremely rare scenarios where e.g. someone's private information was exposed. crates.io, Rust's default package source, does not permit deletion.

- Commit lockfiles to ensure that builds are reproducible, the same dependencies are pulled every time, and a future compromise of a dependency doesn't impact you unless you explicitly update. This is the default behavior for Cargo and npm. The lockfile will also ensure that the dependency's location is preserved, preventing dependency substitution attacks and should ensure that with the first point above that even a yanked dependency can still be resolved.

- Vendor dependencies so that you have a true complete snapshot of things without relying on 3rd parties. This weighs a lot more and is harder to manage over time but is an immediate solution to both of the above points.

On #3, sure. This is reasonable, but there are costs to writing that code that I'll cover later on.

# Just because C/C++ users suffer doesn't mean everyone else has to

I'm going to quote a few of John's paragraphs for full context and then dissect some of them one-by-one:

Rust makes it easy to pull in outside dependencies, and much like in the JavaScript ecosystem, it seems to have encouraged lots of tiny dependencies. That makes it a lot harder to monitor and manage the problem.

But Rust’s situation is even worse than in most languages, in that core Rust libraries (major libraries officially maintained by the Rust project) make heavy use of third party dependencies. The project needs to take ownership and provide oversight for their libraries.

To me, this has long been one of the biggest risks in software. I can write C code that is reasonably defensive, but I have a hard time trusting any single dependency I use, never mind scaling that out.

Properly securing your dependency supply chain is a much harder problem than writing safe C code. Personally, I only pull in dependencies beyond standard libraries if the work I’d have to do in order to credibly replace the functionality is so great that, if I didn’t bring in a dependency, I would choose not to do the work.

C is a lot better than Rust in this regard, but it’s not particularly great. Partially, that’s because the C standard libraries (which I am always willing to use; the core language implementation and runtime is a given) are not at all extensive. People who write a lot of C end up building things themselves once and keeping them around and adapting them for decades, including basic data structures like hash tables.

First of all, I strongly disagree with the sentiment that securing your dependency supply chain is harder than writing safe C/C++ code.

You have to be at least a moderately advanced user in C++/core memory safety ideas to come to the realization that modifying a container while iterating it with iterators is a bad idea, or that there are subtly different ways to zero-initialize a structure that result in subtly different ways of it being zero-initialized (which may or may not include its padding), or that some types of pointer arithmetic/comparisons are undefined behavior.

You don't need to be an advanced programmer to do a short sniff test to see if a dependency you're bringing in to your application looks fairly widely used and trusted by a community. Sure, the XZ backdoor is an extreme example of even experts who were members of the project missed something snuck in over time, but this is not what we're talking about here.

Rust makes it easy to pull in outside dependencies

Honestly? Thank god.

While C/C++ applications generally require fewer dependencies, most of the time you're relying on the project maintainer to provide you with a list of those dependencies and how to install them with your platform's preferred package manager.

Something that I always find myself saying when try to build a C/C++ application from source is "shit I'm missing a header" and general complaints about the build tools themselves. And of course the build/configuration tool tells you what you lack but doesn't tell you what you need to install because that's not its responsibility. The build tool may support building on your favorite OS, but it doesn't know how to install packages on that OS or even what the package is.

So you're left with a terrible error message that can leave you wondering "Do I need to install lib-dev-whatever2 or just lib-whatever2? Is this even available via my OS's package manager?"

Don't forget all of the dependencies you need to install just to install the dependency too: pkgconf, autoconf, autotools, ninja, cmake, whatever, and any other libraries this single dependency may rely on. Kicking the problem into a Dockerfile is also not a good substitution for a quality build tool.

The developer experience surrounding dependencies in C/C++ is so awful that you just default to not using any at all. Or you bring in a "header-only library" that makes integration easy because bringing in multiple external source/header files makes people want to turn off their computer and consider another career.

[Easy dependency usage] seems to have encouraged lots of tiny dependencies. That makes it a lot harder to monitor and manage the problem.

I disagree that the dependency story becomes harder to manage. There are multiple tools to monitor and manage your dependency usage in Rust:

- cargo-tree can tell you your dependency tree

- cargo-geiger can tell you if any of your dependencies in the graph use

unsafe{} - cargo-acl can tell you which crates use

unsafe{}, run build scripts to see if any use network/filesystem, and provides you with API usage information to see if a crate is doing things unexpected. It can even sandbox the build tools. - cargo-audit can tell you if any of your crates are affected by a known security vulnerability and fix the used package version automatically.

These are all possible because Rust's tooling ecosystem is so good. These are not things that are run by default so the argument is a bit weaker, but the fact that they exist means you have the option of using them if you want to. For example, I've seen many CI pipelines that use cargo-audit to ensure vulnerable crates aren't being used.

People who write a lot of C end up building things themselves once and keeping them around and adapting them for decades, including basic data structures like hash tables.

I see this as a bad thing. You're probably going to write bugs and it's going to be hard to fix affected applications. No proper version tracking or update mechanism means that depending on how you use and manage this ad-hoc dependency, tracking where it's used and patching affected programs might be difficult.

A hash table is also not necessarily a "basic" data structure but I would definitely consider it a common data structure. Common data structures and algorithms can still have bugs, and there are many examples of this (and if it's so common why isn't it in the stdlib?). No intent here to shame these folks, but just some examples: smallvec, libwebp's Huffman tree decoding, and glibc's qsort(). (I'm aware that glibc and libwebp would typically be installed using your distro's package manager but that's besides the point.)

So why are we shooting ourselves in the foot by making it difficult to track and manage our dependencies for C/C++, including even our own first-party dependencies?

@Lucretiel summarized this same sentiment fairly well on Twitter:

Quick reminder that I C doesn't have a culture of minimal dependencies because of some kind of ingrained strong principles in its community, C has a culture of minimal dependencies because adding a dependency in C is a pain in the fucking ass.

Rust and Node.js have smaller projects and deeper dependency trees than C++ or Python for literally no other reason than the fact that the former languages make it very easy to create, publish, distribute, and declare dependencies.

This is systemic incentives 101.

# Rust isn't as "batteries included" as other languages

One point John makes is:

Languages like Go and Python that have extensive standard libraries that the language maintainers take responsibility for are actually the best case scenario in my opinion. Yes, more people touch the code, but the DIY economics are often the wrong choice, and having organizations willing to both be accountable, and provide an environment where people can focus on minimizing dependencies if they feel its important, is a good thing.

...

Generally, I think Rust (and pretty much any programming language) would be served well to take ownership of their standard libraries. Pull in all the dependencies, and be willing to take ownership.

I agree with John that having batteries included simplifies things for both new and established users, but I don't think we should be so quick to add more batteries to the collection without sufficient testing.

My understanding is Rust has learned from the mistakes of other languages and explicitly tries not to include things in the standard library that the Rust core team believes don't quite fit, including for reasons of figuring out the API. You simply have more freedom with packages: they're semver-versioned and you can break compat with an appropriate version bump.

You don't necessarily know the warts of an API until you start to really use it widely. Take for example the rand crate. There is no random number generator in the Rust standard library, and rand is the de facto standard crate for this task.

That's a bit odd, no? Random number generation is fairly common and one would think it's in the standard library. There's even a tracking issue for adding one: #27703 (and #36999).

While I agree in principle, putting something into the standard library mostly means that the APIs for it are immutable. You know what's changed in fairly minor but meaningful ways since those issues were closed? The rand crate's APIs. If these had been brought into the standard library as-is we'd be mostly forever stuck with certain warts like Rng::gen_range() accepting 2 args (low, high) instead of the more-natural Range (using low..=high syntax).

Rust itself is still a growing and changing language as well, and it may not make sense to land on an API that would be better once language improvements land. Good luck changing a stabilized API without breaking compat.

# Package management in other languages also suck

Yes, Python has become so popular, that plenty of people use outside dependencies, and there are several popular package managers. However, it’s still in a vastly better place from a supply chain perspective than JavaScript, which has become famous among developers for hidden dependencies on trivially small packages.

There's no way to really sugarcoat this, but Python and Go package management really fucking sucked (Python still sucks, but some semi-recent tools are making it suck less).

So Python has monolithic dependencies... but why? Because the tooling and uploading dependencies is high-friction(I've never uploaded -- maybe it's easier than I think). And we're supposed to praise this? In what world is Python + pip "in a vastly better place from a supply chain perspective than JavaScript" because of this fact either?

- pip dependencies are by default global which causes conflicts with other Python applications, forcing you to use virtual environments. Note: /u/encyclopedist on Reddit pointed out that this has recently changed with PEP 668.

- If pip hits a version conflict within your own project's package graph you're in for a headache

- Packages with native dependencies are a mystery to basically everyone except the package author. Or is this just me?

- There's no strong lockfile containing metadata sufficient for guaranteeing the bits someone installing a project's dependencies for the first time match the bits when the lockfile was generated (i.e. package hashes).

pip in my experience has been so frustrating to use for dependency management that it inspires me to just simply not use dependencies to begin with. Yes there are tools that make this easier, but they are not defaults or even agreed upon by the community.

And before Go had its package management renaissance does anyone remember what it looked like to use dependencies in Go?

You imported a library like this in your code:

import (

"github.com/codegangsta/cli"

)

You use go get to download the dependencies to your local machine, and built the application.

There were no lock files, no versions, nothing. The latest version of the source code was grabbed and used until you updated it which may have had breaking changes. The community had to resort to package proxies to version packages. Today it's pretty insane to think about letting a 3rd party man-in-the-middle your packages and deliver it to you with no integrity checks just to work around warts in the tools.

And what about other languages like C#? NuGet, .NET's package manager, was also terrible.

I don't know how it is today, but around ~2017 while working at Microsoft I discovered that NuGet had a "feature" where the client would reach out to all of your package feeds in parallel to fetch a package and whichever responded first won. I can't find the issue for it on GitHub, but someone had reported this behavior and it was considered "by-design".

Even still when I presented the problem to the NuGet team internally, they did not see it as a vulnerability. The obvious problem here was that we were leaking our internal package names to external package feeds and a name collision could result in the wrong package being used (this was before dependency substitution/confusion attacks were widely known).

NuGet also had no lock files, no integrity checks, and conveniently provides install/build scripts and usually what you're receiving is prebuilt binaries. Code integrity isn't verified and the only thing that would have prevented you from using a completely different binary was Strong naming which is not a security boundary. In fact, I've seen a lot of projects publish their strong name key.

Rust was fortunately blessed from the beginning (pre-1.0, 2014!) with people who knew how to build a package manager. Cargo is not perfect, but it works pretty damn well for the majority of Rust users.

It is because the package management story in Rust is so good compared to other languages that the standard library doesn't need to be as feature-complete. Shipping with a fantastic package manager in 1.0 allowed the community package ecosystem to explode without having to pause and shift towards better or different solutions (NuGet's change to JSON-based projects, Go's shift away from go get using git-based imports to Go modules, and many different Python package managers like poetry, rye, pipenv).

Rust developers are not bleeding from using the tools they depend on and it's absurd to me that this is considered a weakness.

# What about dependency explosion?

Here is an example of an application I'm working on that reads files in a custom filesystem specific to the Xbox 360 (known as XContent / STFS). There's crypto involved for signing the header and verifying file data and conceptually this single file contains many others similar to a tarball or zip file.

It's a CLI application with the following dependencies in its Cargo.toml file:

[dependencies]

# For mmaping the input file

memmap2 = "0.9"

# Parsing arguments

clap = { version = "4.5.4", features = ["derive"] }

# Easy error handling

anyhow = "1.0"

# Data serialization

serde = { version = "1.0" }

# Reading the input file's filesystem

stfs = { version = "0.1", path = "../stfs" }

# Also for reading the input file's filesystem

xcontent = { path = "../xcontent" }

# Date/time operations

chrono = "0.4.38"

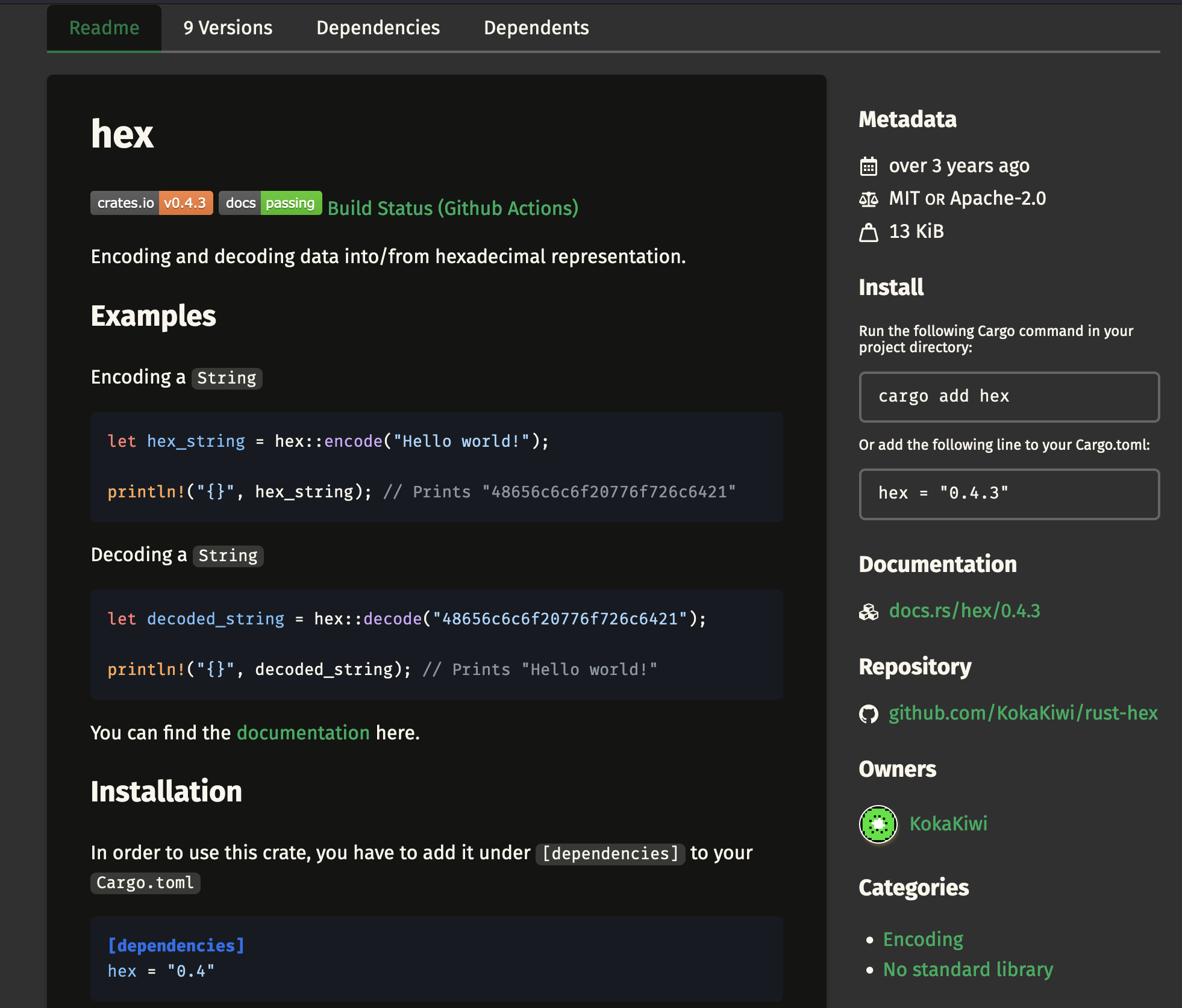

# Converting data to/from hexadecimal

hex = "0.4.3"

# Converting file sizes to something human-readable

humansize = "2.1.3"

# Serializing data to JSON

serde_json = "1.0"

According to cargo deps-list this results in 102 dependencies from the 10 direct dependencies I specified. cargo depgraph produced this graph:

Click for a larger image

# The sniff test

I've mentioned my "quick checks" or "sniff test" a couple times in this blog post, so it's worth calling out what it is.

I 100% did not audit all 102 of these dependencies in the above graph, but for each of the 10 I directly brought in to my application I looked at the author to see if I knew of them, looked at their project setup, and decided their goals align with mine which led me to using the crate. I've passed on crates that to me looked like someone not necessarily intending for others to use their work, or simply did not pass my vibe check.

Here is what my personal flow looks like:

- Do a search for the topic I'm interested in

- Check the crates.io page

✅ The crate has good examples and information. I don't recognize the author, but that's not terribly uncommon.

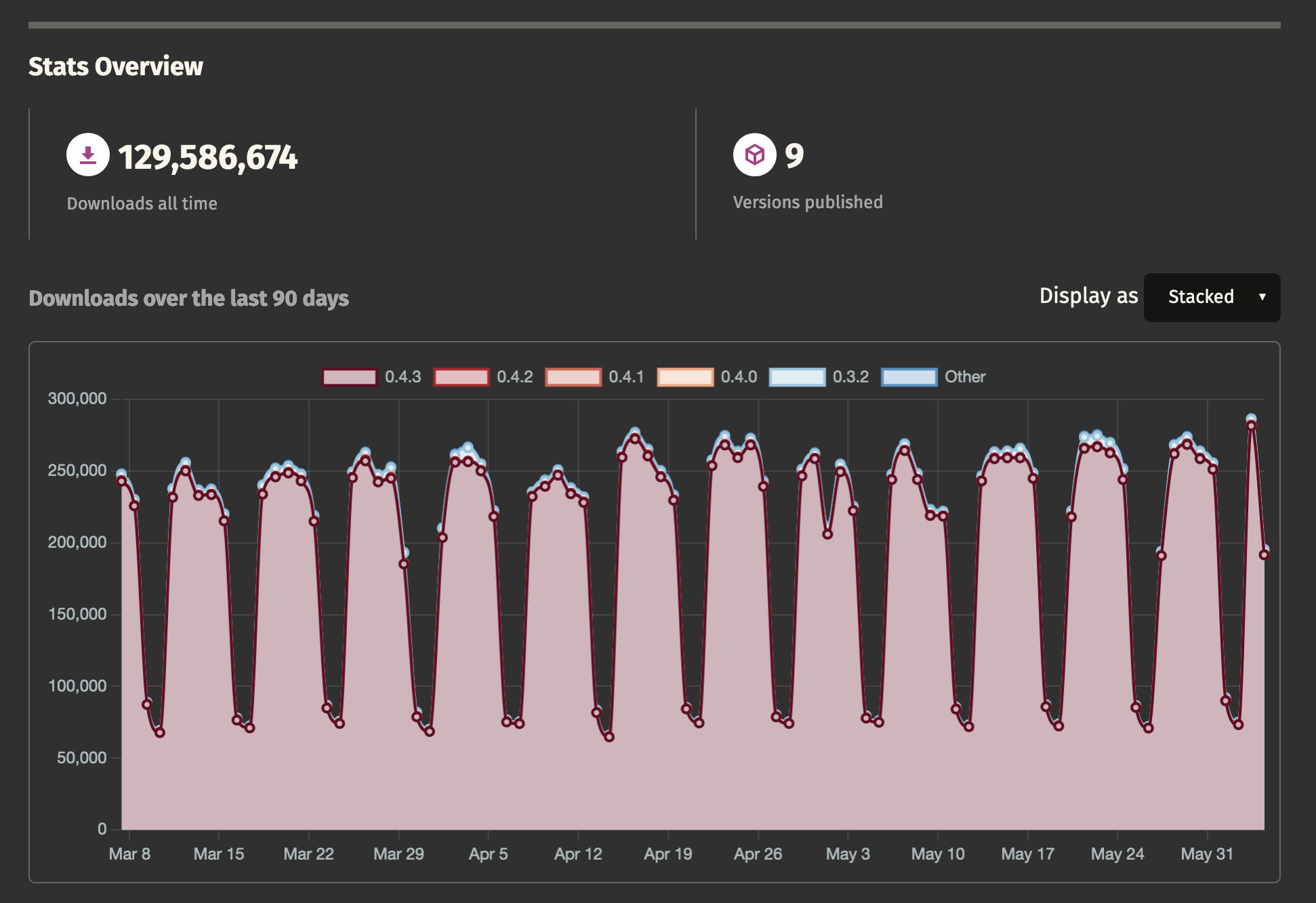

- Check the crate's stats to get an idea of how widely used it is

✅ Tons of usage. These numbers can be gamed, but probably not to this level.

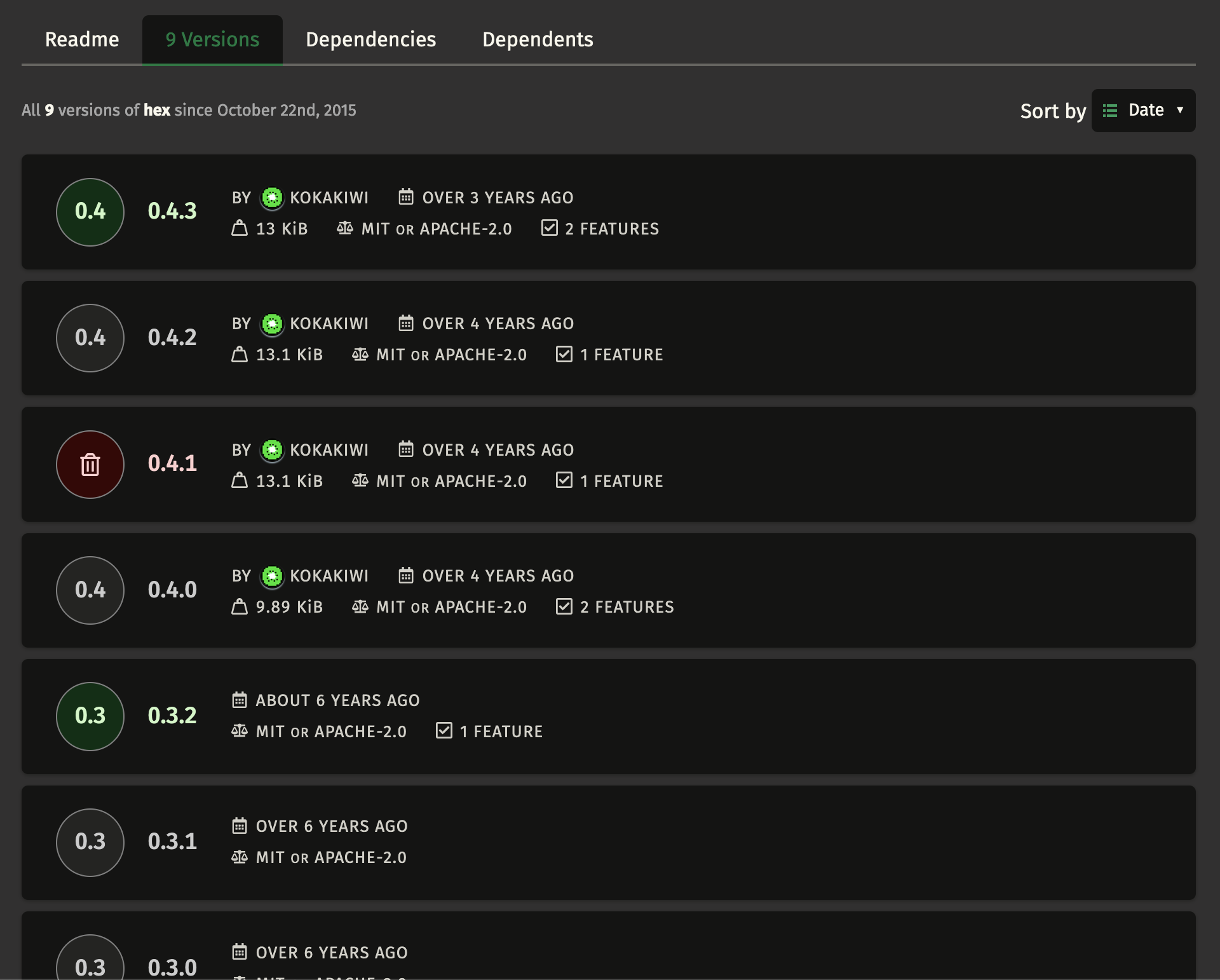

- Check the versions.

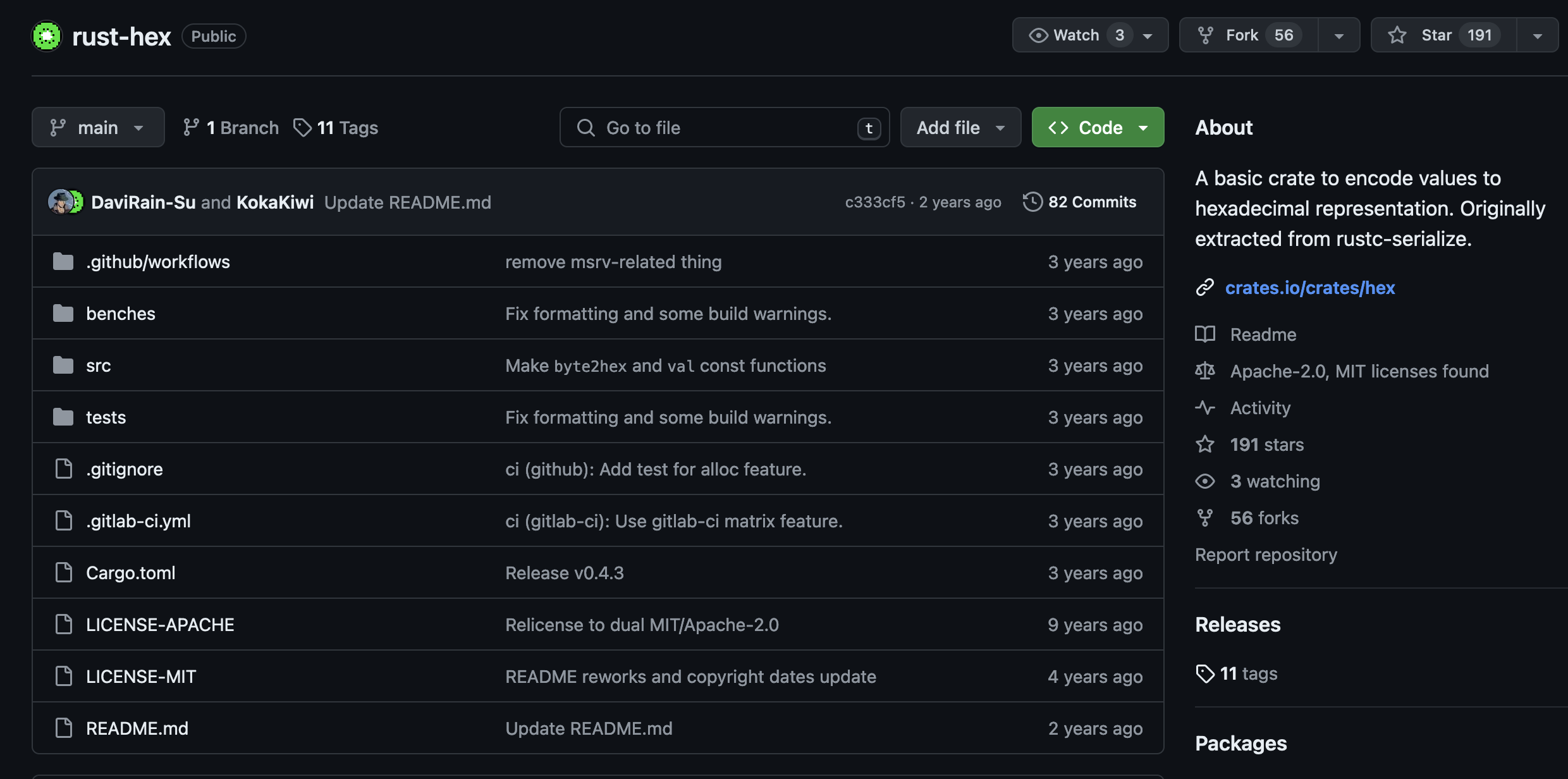

✅ 9 versions since its original release 8 years ago. The last release was 3 years ago. The author isn't changing stuff all the time which is good as I don't expect a hex crate to have heavy code churn.

- Check who is using this crate to see if I recognize any of them

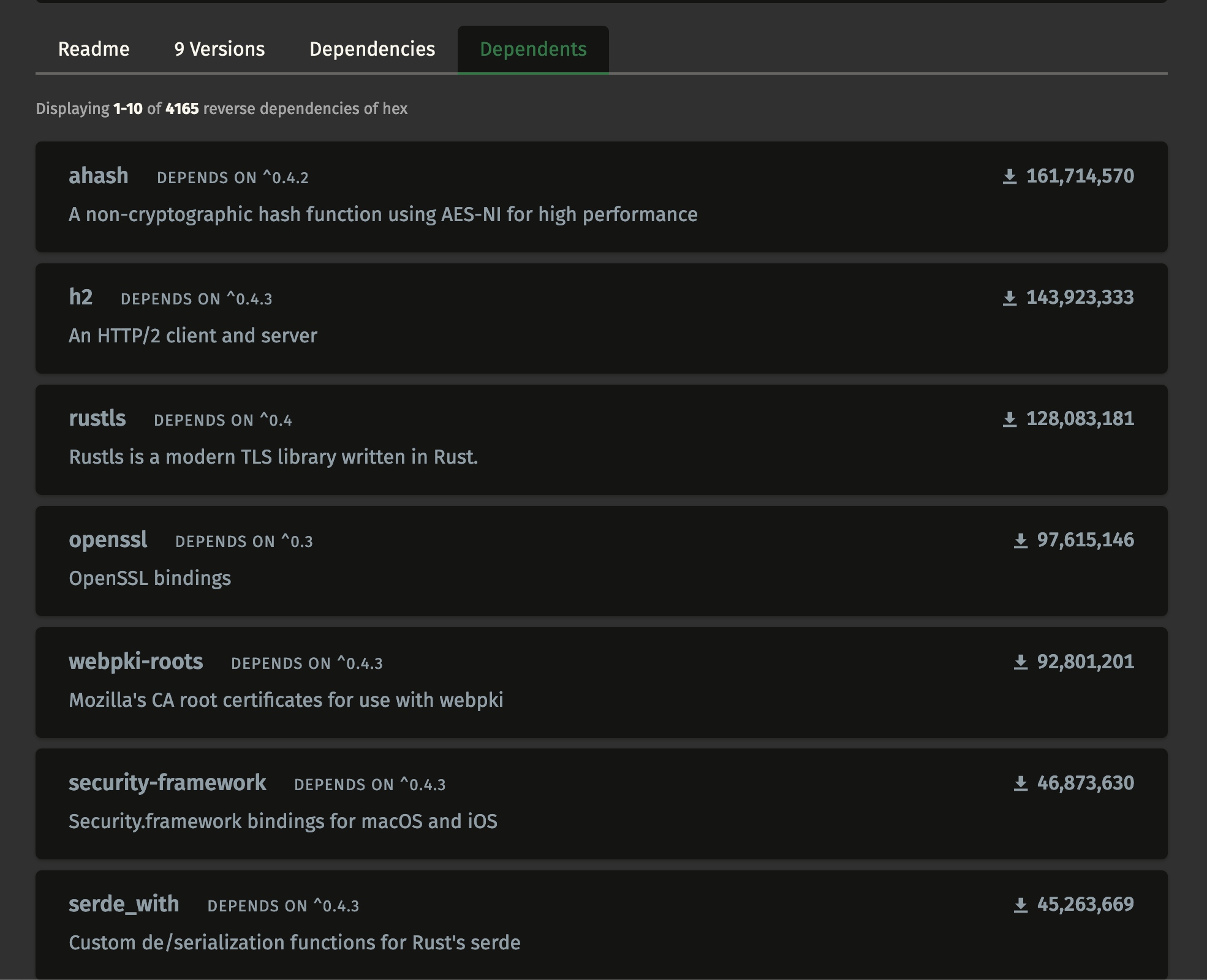

✅ The hex crate has over 4,000 other crates depending on it and I recognize all of the top 5 biggest users.

- Check the repo

✅ This is not a great example but the hex crate has some stars, the active development about matches the crates.io page (keep in mind the repository doesn't have to match what's uploaded to crates.io!), and the project looks decently put together. There's also no build.rs script that I need to check out.

The crate passes all of my standard checks! I feel comfortable pulling the crate into my repository

# Economic factors

Something John mentions multiple times is weighing "economic factors" when considering what language or dependencies to use.

Avoid unnecessary dependencies. I will leave ‘unnecessary’ vaguely defined here; you need to be educated and judge all the economic factors. But note that, there are often other benefits to fewer dependencies, from shorter build times to less surface to test, to less risk from API changes or bugs from downstream dependencies.

Are all of these 10 crates I used above strictly necessarily? No. I could get away with writing my own hex converter, human-readable size converter, command-line argument parser, drop mmap support, drop support for chrono date/time, and rewrite to use standard Result<T, E> instead of using anyhow. This is what such a Cargo.toml would look like:

[dependencies]

# Data serialization

serde = { version = "1.0" }

# Reading the input file's filesystem

stfs = { version = "0.1", path = "../stfs" }

# Also for reading the input file's filesystem

xcontent = { path = "../xcontent" }

# Serializing data to JSON

serde_json = "1.0"

But you know what I get from splurging on 6 extra deps?

I can just write my fucking code. That's the biggest economic factor I care about.

I don't have to worry about making my argument parser print out help and keeping its flags and info up-to-date and manually pretty. I don't have to leave the user with a shitty DateTime field because I can't write a good one for them since my app doesn't revolve around dates. I don't have to write boilerplate for bubbling up errors. The overall quality of the application and my dev experience is improved.

hex and humansize are arguably my application's left-pad. Converting to/from hex is not terribly complex and converting a number of bytes to the best unit of KB/MB/GB is extremely easy. In fact, I'm pretty sure I originally wrote it for this project and then removed it. These dependencies do one task that's simple enough for me to write but I didn't.

Why? Because each handles some edge cases that may matter for me, and I'm not wanting to spend 30m of my time writing something that's not core to my application when someone already wrote the code and did it better than I would in those 30m. Instead I took 3 minutes to search around to find the crate, ensure it fit my needs and to sanity check it looked kinda legit, and then used it in my application.

I got. Shit. Done.

I will say that there have been times where I've compiled something and thought, "Holy shit 500+ dependencies?" But to me this isn't a signal of it's security but rather bloat and complexity. I have to think about everything the application does, its complexity, and consider if it's just bloated for no reason or if there is good reason for having so many dependencies. This can impact my judgement on the application's quality and how likely I am to use really use the tool.

@Lucretiel said something else recently on Twitter said something that loosely fits into this topic:

It’s a good thing we’re keeping our dependency count low, I think to myself, as I read about how my UI framework also provides threads, networking utilities, data structures, floating point math, D-Bus, cryptographic utilities, geographic utilities, and a Bluetooth implementation

Bloat is everywhere. You just need to know how to look for it.

# Circle of trust

Anyway, the more dependencies you have, the larger your circle of implicit trust is, the larger your attack surface is, and the more supply chain risk you’re taking.

I'd rather assume an author of a crate that looks like it provides what I need has non-malicious intent than the other way around. Maybe that perspective will change if I ever get burned and my laptop gets ransomwared because I missed a build.rs file or a proc macro that does sketchy things.

But consider for a second: do you consider your OS as part of your circle of trust? It's unlikely you'll ever get backdoored by your OS, but bugs are certainly present and depending on your threat model a vulnerable OS means a problem for you.

Do you know how much attack surface there is with say image parsing on iOS/macOS?

You can choose to not bring in libjpeg/libpng/libwebp and just use ImageIO (which is used by UIKit/CoreGraphics). Easy! Except you now have at least 30 different image formats on your attack surface that you didn't know about. And there's no way to turn them off. And now you're stuck ensuring that the image you're parsing is a trusted image format.

You might be screaming, "But Apple is trusted! And Apple publishes updates!"

Ok? Did you validate how many of those updates are backported to major iOS versions used by your users? Did you audit Apple's closed-source lib and discover this attack surface and then weigh the economic costs of not using it? I mean, ImageIO is mostly just a wrapper around libjpeg and libpng, so why not just use them directly?

Likely answer: Because it's convenient and you might not care about the problems I am describing because you aren't some security nerd.

# Closing thoughts

I would like to thank John for sharing his thoughts and perspective. I do outright agree with some his points:

- Avoiding unnecessary dependencies may be better long-term for better compile times and less potential problems down the road. This is a tradeoff worth considering, but to me is a minor point.

- The bigger your dependency graph, the bigger your single-points of failure. I see this as a tradeoff for rapid development.

- Understand what makes sense for your team and your own threat model.

But I disagree with some of the foundational arguments like:

C’s advantage in terms of lack of dependencies (which can come with a lower attack surface in general) is large, but still doesn’t make it the right economic choice in the first place. It might still be wiser to choose Rust when all economic factors are considered, but the security argument is just not one I find compelling enough.

The security risk of dependency use is simply not one I find compelling enough to select C over Rust, and certainly is not scarier than a buffer overflow. C lacking first-class support for dependencies should be considered a strong disadvantage since you can't even get good support for 1st-party dependencies.

The benefits Rust provides as a language are already enough for a lot of people to select it over C -- myself included. A stellar default package manager and build tool makes it all the better to use. In my opinion "dependency usage" should be a minor footnote (and John explicitly says to weigh these kinds of factors yourself).

Additionally, I'd argue that a critical mem safety issue is statistically way more likely to happen and can have critical impact even with modern mitigations. Some of the memory safety bugs that we're finding are old enough to drink in the US, showing that they can be very difficult to find. The xz backdoor required around 3 years worth of effort to attempt to sneak into the application and was discovered in less than a week after it went live.

Don't live in fear of dependencies. Do what provides the least friction for you to accomplish the engineering you enjoy doing within your personal or team parameters.